Introduction

In today’s globalized world, geographical boundaries have become more fluid than ever, thanks to media, migration, and communication technologies. Diaspora communities—formed as a result of migration, exile, or displacement—play an increasingly significant role as cultural agents, particularly in representing the art and culture of their countries of origin. But a central question arises: Can the diaspora represent the culture and art of the homeland as it truly is? Or is the cultural output of diaspora communities essentially a reimagined version, shaped by the conditions and perspectives of life away from home?

This article, informed by academic studies and socio-cultural theory, critically examines this question through a multidisciplinary lens—drawing from sociology, postcolonial studies, and cultural anthropology, and looking at concrete examples from contemporary popular culture.

Diaspora as a Cultural Carrier and Mediator

In social science literature, the diaspora is not simply a group of migrants but a multi-layered cultural and psychological phenomenon. Stuart Hall, the British cultural theorist, used the concept of “fluid identity” to describe diaspora communities, emphasizing that their identities are forged at the intersection of past and present, homeland and exile, tradition and innovation (Hall, 1990).

In this light, the diaspora is not merely a preserver of tradition, but also a reinterpreter of it. Cut off by time and space from the everyday realities of the homeland, diaspora communities often build idealized or imagined versions of their native cultures—versions that may differ significantly from the homeland’s contemporary reality. These imagined identities often become the basis for their artistic and cultural representations.

Case Study: Ed Sheeran’s “Azizām” and the Problem of Misrepresentation

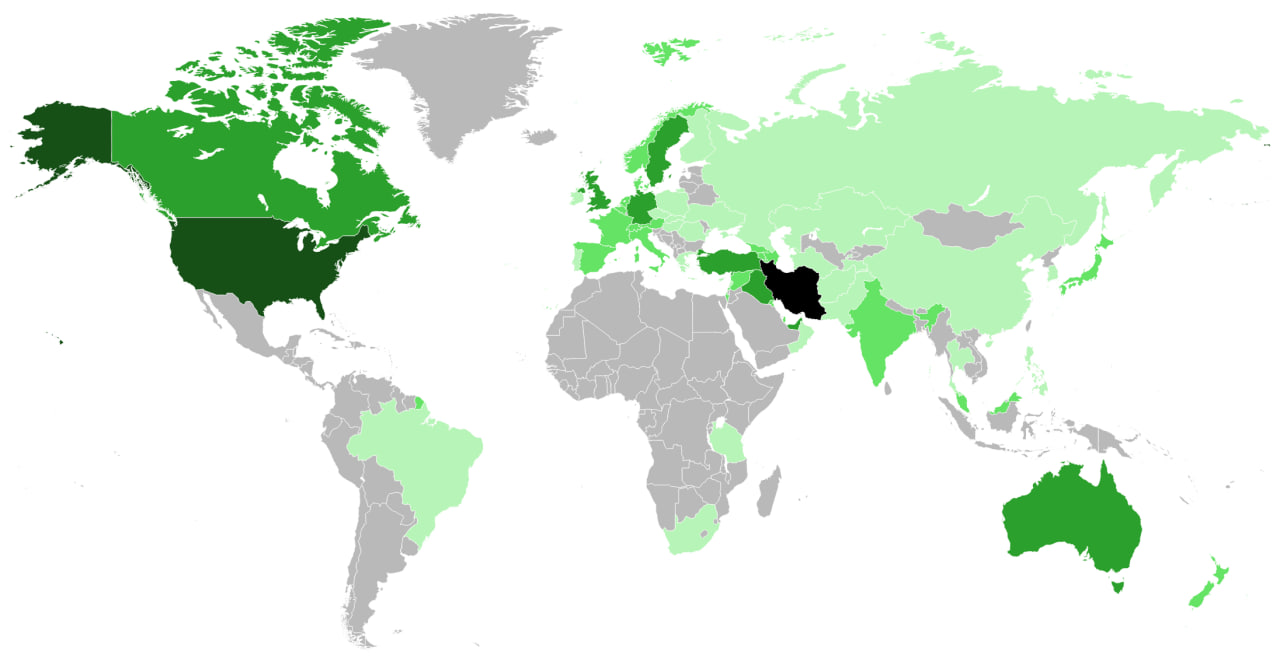

A recent and illustrative example is British pop singer Ed Sheeran’s song “Azizām”, which purports to draw inspiration from an Iranian wedding. While seemingly a tribute to Iranian culture, the final product bears aesthetic and symbolic elements more reminiscent of Arab cultural tropes than authentically Persian ones—leading to criticism from Iranian viewers who noted the misalignment with what is commonly recognized as Persian architecture, rituals, and visual identity.

One might explain this through Edward Said’s theory of Orientalism (Said, 1978)—the construction of a simplified and exoticized “East” by the Western gaze. But when such representation is shaped in collaboration with or influenced by Iranian diaspora members, the issue becomes more complex. Is this misrepresentation the result of distance and detachment? Or does it reflect the unique cultural reality of the diaspora—one that blends Iranian heritage with the cultural codes of the host society?

Cultural Loyalty: Historical vs. Experiential

Here we must distinguish between historical loyalty and experiential loyalty to culture. Historical loyalty implies an effort to preserve rituals, symbols, and aesthetics in their most “authentic” form. Experiential loyalty, on the other hand, is about staying true to one’s lived experience—however hybrid or fragmented it may be.

Consider the example of third-generation Iranian-Americans in Los Angeles. Their conception of “Iranian-ness” may be built on family anecdotes, nostalgic media, or household rituals—not direct exposure to Iran’s current cultural life. When such individuals create art or music that claims to be Iranian, they are in fact reflecting a version of Iranian culture that is filtered through American life, memory, and imagination.

Diaspora: Alternative Voice or Disconnected Echo?

A key challenge in evaluating diaspora cultural production lies in the question of legitimacy: Can the diaspora speak for a culture it may no longer directly experience? Or, more provocatively, are these voices merely reflections of the migration experience rather than the culture of the homeland?

Studies of the African and Caribbean diasporas in the U.S. and U.K. show that cultural products like hip-hop or Afro-Caribbean dance are less about preserving tradition and more about articulating new identities rooted in exile, marginalization, and cultural fusion (Gilroy, 1993). Similarly, Iranian diaspora art may not aim to replicate Iran’s national identity but rather express the dislocations and hybridities that come with migration.

In this sense, diaspora art is often not about representing culture, but about producing culture—new, syncretic, and context-specific.

Conclusion: Culture as a Living Process

Culture is not a fixed essence that can be transplanted across borders intact. What the diaspora represents is not a carbon copy of the homeland’s culture but the product of a complex process—where tradition is renegotiated in new contexts, and meanings shift.

Rather than criticizing diaspora representations for being inauthentic, we should recognize them as articulations of new cultural forms that speak to the realities of living between worlds. These hybrid expressions are no less valid; they are essential contributions to the evolving narrative of cultural identity.

Ultimately, the diaspora—especially its second and third generations—is not merely an ambassador of the old, but a site of innovation, where fragments of past and present, East and West, are woven into something entirely new. It is the role of cultural analysts to understand these transformations not as distortions but as emerging grammars of lived experience.

By: Kasra Aliha

Architect, Digital Artist, and Art Researcher