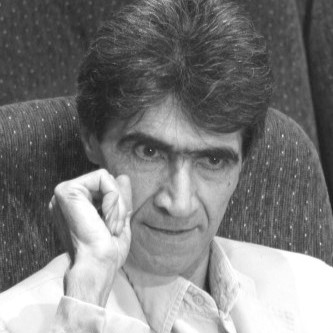

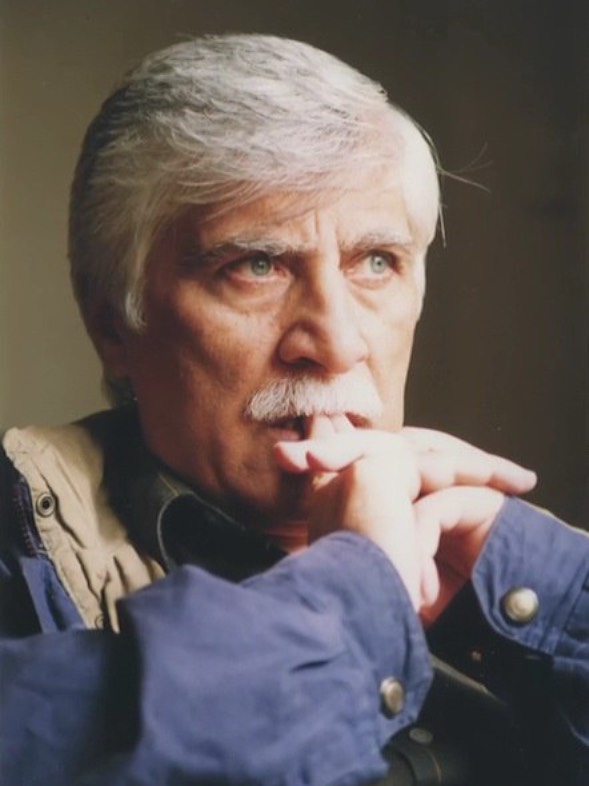

On the morning of October 14, 2025 (Mehr 22, 1404), Nasser Taghvai — filmmaker, writer, photographer, and teacher — passed away at the age of 84.

Born in Abadan, Taghvai was one of the most visionary figures in Iranian cinema, whose works — from Bad Jen to Kaghaz-e Bi Khat (Unruled Paper) — bridged anthropology, literature, and poetry.

His death, like the long silence that overshadowed the later years of his life, mirrors the fate of a generation that struggled to live freely amid censorship and constraint.

His wife, actress Marzieh Vafamehr, wrote:

“Nasser Taghvai, an artist who chose the hardship of freedom, has finally found release.”

From the South: Words Before Images

Born in 1941 in the oil city of Abadan, Taghvai grew up surrounded by workers, heat, and the music of the Persian Gulf.

He once said:

“I love Iran because it’s my homeland, I love Khuzestan because it’s my province, but I’m in love with Abadan — it’s where I was born.”

Encouraged by an early teacher who gave him his first camera, he began his artistic journey with photography — the medium that shaped his eye before cinema did.

After finishing high school, he studied Persian Literature at the University of Tehran, believing that “literature is the mother of all arts.”

His first published work was the short story collection “The Summer of That Year”, depicting the lives of dock workers with social realism and compassion. The book was banned soon after publication — a ban that nudged him toward cinema.

Learning Cinema with Golestan and National Television

In the 1960s, through an introduction by Jalal Al-e Ahmad, he joined Ebrahim Golestan’s studio, where he assisted in Brick and Mirror.

“You can’t learn cinema by just watching films,” he once said. “You have to breathe alongside real filmmakers.”

Later, with Farrokh Ghaffari’s recommendation, Taghvai joined the National Iranian Television as a documentarian.

There, his poetic eye met his anthropological curiosity, resulting in a series of groundbreaking ethnographic films:

Bad Jen (The Wind of the Spirits), The Thursday Market of Minab, Palm Tree, and Arbaeen.

Bad Jen, narrated by Ahmad Shamloo, remains one of the most haunting visual documents of southern Iran — a masterpiece of ethnographic cinema.

Feature Films: A Trilogy of Anxiety and Fate

Taghvai’s first feature, “Calm in the Presence of Others” (1969), adapted from a story by Gholamhossein Saedi, portrayed the psychological breakdown of a retired colonel in a decaying society.

The film was banned, but is now regarded — alongside Mehrjui’s The Cow — as a cornerstone of the Iranian New Wave.

He followed it with Sadegh Kordeh (Sadegh the Kurdish) in 1971 and The Curse in 1973 — a trilogy exploring alienation, revenge, and social disintegration.

His collaboration and friendship with writer Gholamhossein Saedi deeply shaped his vision; their travels to southern Iran inspired both Saedi’s The People of the Wind and Taghvai’s Bad Jen.

Uncle Napoleon: Satire, Memory, Immortality

In the mid-1970s, Taghvai adapted Iraj Pezeshkzad’s celebrated novel My Uncle Napoleon into a television series.

Its nuanced humor, critique of paranoia, and nostalgia for pre-war Iran made it one of the most beloved works in Iranian television history.

Even today, half a century later, its lines and characters live on in public memory.

“I made Uncle Napoleon for the people,” Taghvai said, “because people deserve to see themselves reflected — even in satire.”

After the Revolution: Censorship and the Tempest

After 1979, Taghvai’s life and career were deeply affected by political upheaval.

He began pre-production on Kuchak-e Jangali, a TV series about the legendary freedom fighter Mirza Kuchak Khan, but was dismissed midway.

In 1986, he directed his cinematic masterpiece, Captain Khorshid, a southern adaptation of Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not, which won the Bronze Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival.

Three years later came “Ay Iran” (Oh Iran!) — a dark comedy set during the final days of the Pahlavi era.

But soon after, Taghvai fell silent again. His independence and refusal to compromise left him isolated in an industry increasingly constrained by politics.

Unruled Paper and Bitter Tea: The Final Chapters

In 2001, Taghvai returned with “Kaghaz-e Bi Khat (Unruled Paper)”, an intimate story of marriage, writing, and unfulfilled dreams.

The film won the Special Jury Prize at the Fajr Film Festival, which he famously refused to accept.

Two years later, he began “Bitter Tea” in Khuzestan — a film about the Iran-Iraq war that was halted midway.

“It seems war belongs only to those with official permission to talk about it,” he said bitterly. “But that war happened on my land — I lived it with my own flesh.”

From then on, he stopped making films, devoting himself to photography, teaching, and quiet defiance.

The Silent Rebel

In his later years, Taghvai spoke openly about censorship and the creative paralysis it caused:

“They say censorship makes art grow — like in Stalin’s Russia. But they never mention how many works were never written. Pre-Stalin Russia was the land of literature. What was left after?”

And elsewhere:

“Many of us haven’t been able to make films for decades. Why is no one ashamed of that?”

A White Farewell to the Captain

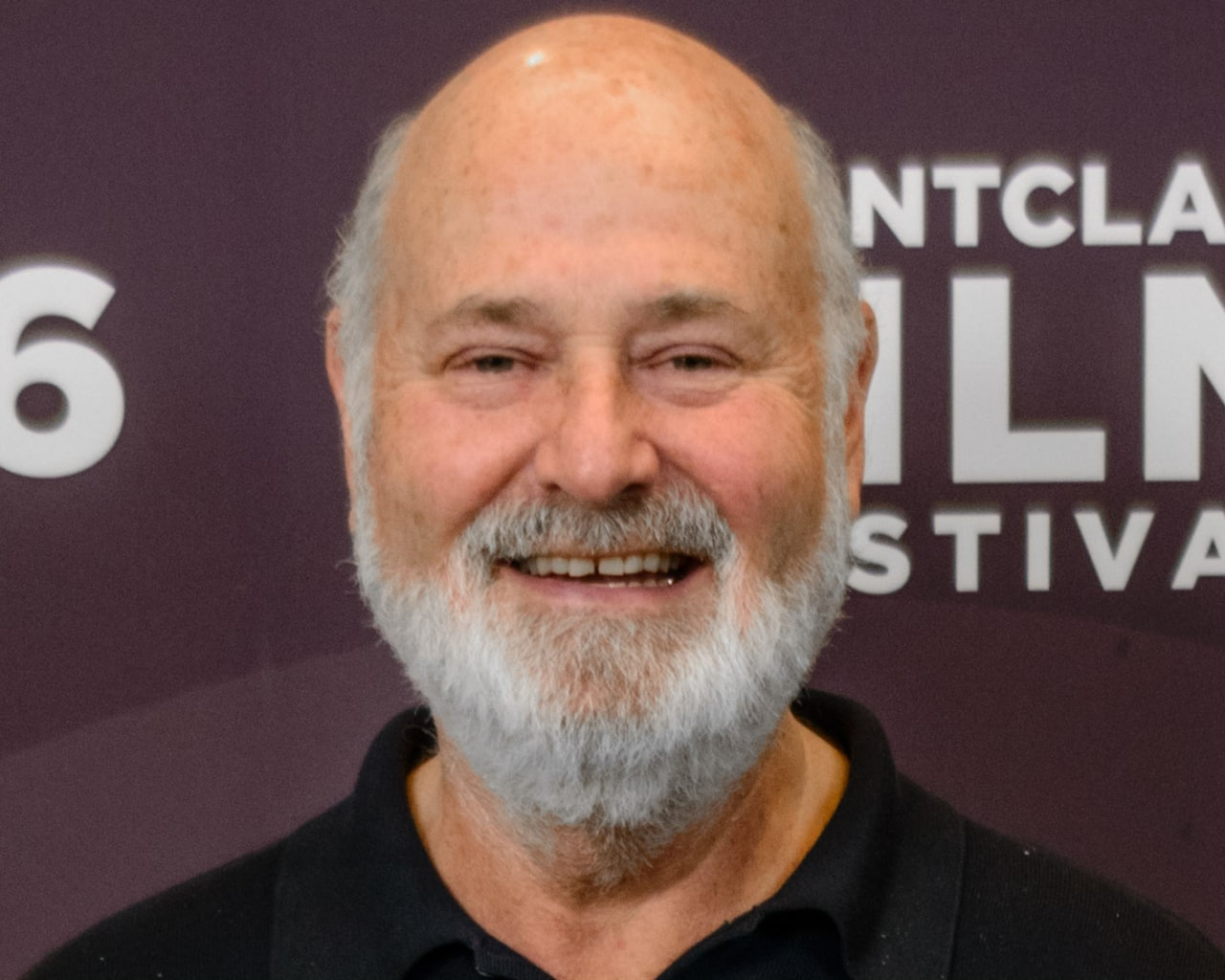

On October 16, 2025 (Mehr 24), Nasser Taghvai’s body was carried from the House of Cinema in Tehran amid artists and admirers dressed in white — per his own will.

He was laid to rest at Emamzadeh Taher Cemetery in Karaj.

Among those present were Katayoun Riahi, Siros Alvand, Gohar Kheirandish, Saeed Poursamimi, and Azita Hajian.

He had asked that people wear white, not black — to celebrate liberation, not mourn loss.

Legacy: The Image of Iran Through the Mirror of the South

Taghvai’s cinema was a cinema of the ordinary Iranian, where poetry met politics, and local culture became universal.

He portrayed the South not as a periphery, but as the heart of Iranian identity — humid, wounded, alive.

Though censorship and solitude silenced many of his dreams, his small body of work remains among the most literary, intelligent, and enduring in Iranian film history.

He once said:

“I’ll never become a professional. If I can’t make films, I’ll write; if I can’t write, I’ll take photos. What matters is that whatever I do, it comes from within me.”

Today, as Iranian cinema mourns him, his words echo once more:

To live freely — that is the hardest, and highest, form of being an artist.